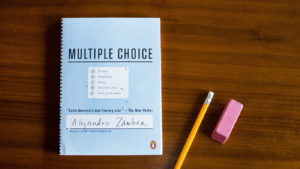

Zambra, Alejandro. Multiple Choice. Penguin, 2016. Paperback. $16.00.

Simply put, the Chilean writer Alejandro Zambra‘s book Multiple Choice is a fantastic experiment in form. As someone who teaches creative nonfiction at the university level, I spend a lot of time discussing the way form and content interact. My classes draw heavily on the work of Brenda Miller and her 2011 AWP article “The Case against Courage in Creative Nonfiction.” In that article, Miller explains, “The conscious use of form can sometimes be the only way certain kinds of truths can be approached at all…As poetry teachers often witness, when a [writer’s] mind is engaged with the rules of a villanelle or a sestina, oftentimes the most creative and heartfelt content arises” (2). Form does not simply shape content; it creates and becomes content too. Zambra’s book exemplifies Miller’s claims, particularly in the way form and content blend together in the structure of a five-part, standardized exam. Zambra employs and manipulates the conventions of the exam to explore themes that include family, politics, marriage, authority, and agency.

Multiple Choice capitalizes on the irony that all standardized exams possess: despite the fact–and it is a fact–that all human beings differ from one other in numerous ways, educators and governments create exams that attempt to assess them on equal grounds. In other words, regardless of shape, all pegs being assessed by the exam must fit through the same round hole.

Zambra’s exam, on the the other hand, increasingly resists standardization in order to conform to and reflect the individuality and subjectivity of both examiner and examinee. As a result, the reader’s journey through this assessment presents more than few challenges. The questions at times are ridiculous and impossible to answer. In the process, they reveal insights about the contradictory nature of human agency and the absurdity of experience. For example, in the “Sentence Order” section, the exam asks questions that direct the examinee to put statements A-E in the right chronological order. The catch is that the statements can be read in any order and still make sense, implying that there is no single right answer to these questions. Thus, these questions draw the reader’s attention toward the artificiality of the constraints placed upon the examinee. This tends to be a theme throughout the book. Even when a question present answers that are obviously incorrect, there remain multiple answers that might fit. The idea that there can only be one right answer is surely an illusion.

Question 74, however, takes a different perspective. In this case, examinees do not have more agency than the exam allow them to believe. On the contrary, they have less. Question 74 provides five alternatives (A-E, as usual), but the answers are all the same:

(A) You weren’t educated, you were trained.

(B) You weren’t educated, you were trained.

(C) You weren’t educated, you were trained.

(D) You weren’t educated, you were trained.

(E) You weren’t educated, you were trained. (76)

As a result, it still does not matter which one the examinee selects, and yet in reality, there really is no choice at all. The idea of agency in this instance is itself the illusion. Still other questions are so complex that they require the examinee to sift through a series of alternatives before they can even answer the question.

The challenge that Multiple Choice presents is a significant one, namely what is this about? I do not know yet. Read as a commentary on the nature of human existence, the piece suggests that even those who are in charge of asking the questions, the really difficult ones, frequently have no idea what the answers are either and are only guessing at what they might be. For example, question 82 is so complex that the A-E options are actually arbitrary combinations of a list of 12 other potential ways to end the sentence “The ending of this story is, without a doubt:

I. Sad

II. Heavy.

III. Ironic

IV. Abrupt

V. Immoral

VI. Realistic

VII. Funny

VIII. Absurd

IX. Implausible

X. Legalistic

XI. Bad

XII. It’s a happy ending, in its own way.” (87)

The potential answers are arbitrary to say the least (88):

A) I, II, IV

B) X

C) All of the above

D) VIII and XI

E) XII

The question is actually far too complex to be dealt with in the conventional A-E formula. To really do justice to this outwardly simple “finish this phrase” kind of question, one would require a book large enough to hold all of the possible permutations of the twelve options supplied. Instead, the exam’s creator sticks to the simplistic conventions of the exam, providing only five arbitrary options when hundreds are needed. The effect of these odd answers exposes the smallness of the examiner’s world view. The authority of the examiner is not backed by knowledge, but by uncertainty, in spite of their proffered phrase “without a doubt.” They are looking for answers to the big questions because they do not have them, just like everyone else, and that all by itself is enough to bring them to the level of the examinee. Before we can find the answers to those big questions, we need to at least acknowledge that even simple questions regarding human behavior and interactions require a more nuanced approach to and respect for their inherent complexity. Without that acknowledgement, we will remain ill-equipped to answer even the simplest of life’s questions.

I hope to get a chance to use this text in my courses someday, specifically as a think-piece regarding the connections between content and form and how the areas of creative writing influence each other. I love that Zambra operates within such a confining form. He raises big questions about the human experience, while simultaneously using those questions to break the form apart, pointing out just how artificial social constructs (like writing conventions) tend to be.

Work Cited

Miller, Brenda. “The Case against Courage in Creative Nonfiction.” AWP, October/November 2011.

Reviewed by Jeff Howard